“Americans believe in the reality of ‘race’ as a defined, indubitable feature of the natural world. Racism–the need to ascribe bone-deep features to people and then humiliate, reduce and destroy them–inevitably follows from this inalterable condition… But race is the child of racism, not the father.”

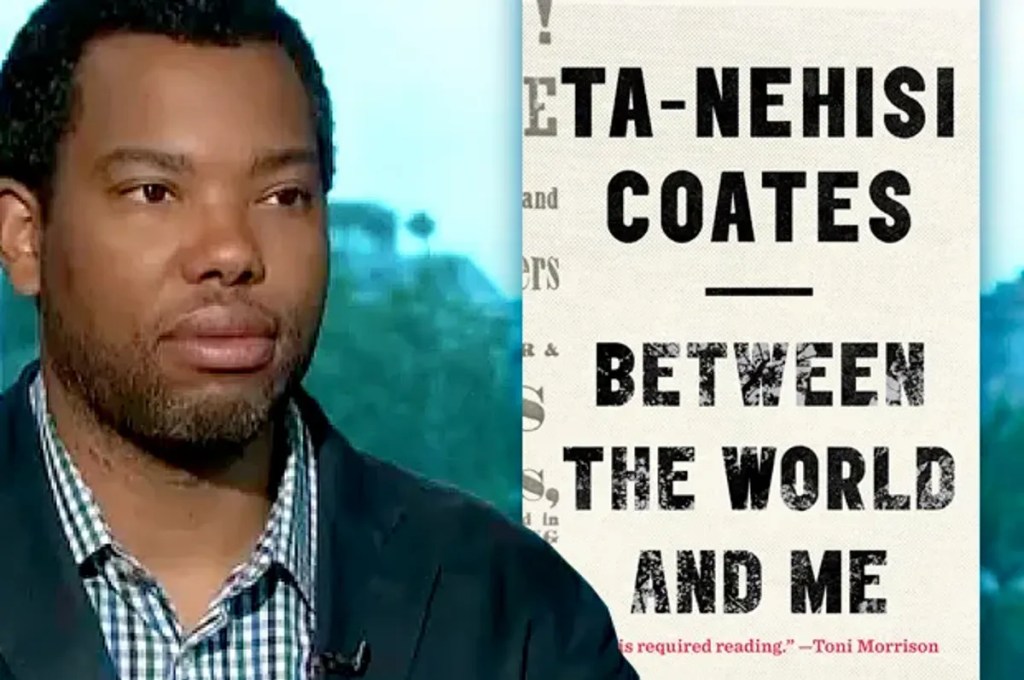

Ta-Nehisi Coates. Between the World and Me. (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2015), p. 7

In this quote, Ta-Nehisi Coates suggests that race is not the cause of racism, but rather its product—a claim that sounds profound until it is examined with the scrutiny it deserves. This is not merely a case of getting the cart before the horse; it is a case of denying the horse ever existed while still riding in the cart.

To say that race was created by racism is to ignore the undeniable fact that human beings have always recognized differences—be they in language, culture, or appearance—long before any modern ideological construct of racism was formulated. The Bible itself, long predating the modern obsession with racial politics, acknowledges that people were divided into nations and tribes (Genesis 10:32). But division does not necessitate oppression. The fact that people belong to different groups does not mean they must be in perpetual enmity.

Furthermore, Coates’ claim does not hold up historically. If racism created race, then one must ask: why do different groups, from ancient China to medieval Europe to pre-colonial Africa, all have their own sense of identity based on lineage, geography, and culture? Were they all victims of some global conspiracy of racism? Or is it simply human nature to recognize distinctions? The latter seems far more in line with both logic and historical evidence.

If anything, history suggests the opposite of what Coates claims—tribalism and ethnocentrism existed before any pseudo-scientific justification for racial superiority was ever concocted. The Israelites and Egyptians distinguished themselves from one another not because of 18th-century racial theories, but because of tangible cultural, religious, and national differences (Exodus 1:9-10). It was not “racism” that created these distinctions but rather these distinctions that sometimes led to conflict.

Moreover, there is a deeper problem with Coates’ formulation: it assumes that racism is an inevitable byproduct of race. But human history, and even American history, suggests otherwise. The United States, despite its racial struggles, has also been the site of immense racial progress—progress made not by erasing the concept of race, but by rejecting the idea that it defines one’s identity or destiny. It was not the denial of race but the affirmation of human dignity, rooted in principles far older than any racial ideology, that led to the abolition of slavery and the civil rights movement (Acts 17:26—”He hath made of one blood all nations of men”).

If anything, the danger lies not in acknowledging human differences, but in using those differences as a cudgel to divide people further. Coates’ framing does not challenge racism; it reinforces it by making race the inescapable prism through which all human interactions must be viewed. Rather than liberating people from racial determinism, his argument chains them to it.

History, logic, and biblical wisdom point to a different conclusion: race is not the child of racism. Race, as a recognition of human diversity, existed long before anyone sought to exploit it for evil ends. It is not race that must be eliminated, but rather the poisonous ideology that insists it is the defining feature of human identity.

In Christ’s service,

~JFH

Leave a comment