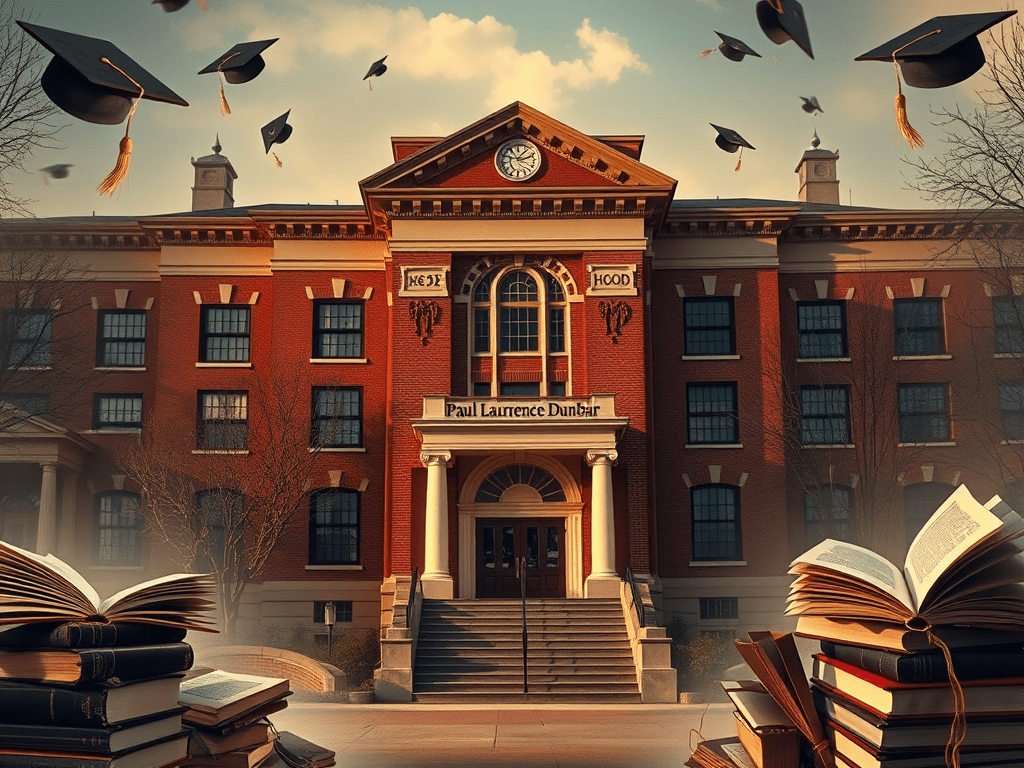

Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, established in 1870 in Washington, D.C., was once a beacon of African American academic achievement. Named after the renowned poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, the school was created to offer educational opportunities to Black students during an era of pervasive segregation and racial discrimination. Over the course of the 20th century, Dunbar transformed from a highly successful institution into a struggling, low-performing school. This essay will explore the factors contributing to Dunbar’s dramatic rise and fall, incorporating insights from economist and social theorist Thomas Sowell, whose work on education, race, and urban policy offers a critical lens for understanding the challenges that led to Dunbar’s decline. Sowell’s arguments, particularly his focus on cultural, economic, and policy-driven factors, provide valuable context for assessing the broader societal forces at play in Dunbar’s trajectory.

The Rise of Paul Dunbar (1870s–1930s)

When Paul Dunbar High School was founded in 1870, it became the first public high school for African Americans in Washington, D.C., at a time when most Black students had no access to formal education. The school’s establishment was part of a larger movement for African American advancement in the post-Reconstruction era, where education was seen as a critical means of economic and social mobility. Dunbar quickly earned a reputation for academic excellence, offering a rigorous curriculum in subjects like the humanities, sciences, and arts.

In the early 20th century, the school produced an extraordinary number of successful and influential Black leaders. Graduates included prominent figures such as Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, U.S. Ambassador Andrew Young, and civil rights activist Charlotte Forten Grimké. These individuals went on to break barriers in law, politics, and society, and their success reinforced Dunbar’s reputation as one of the finest schools for Black students in the country. The school’s success during this period can be understood through the lens of Thomas Sowell’s argument in Race and Culture, where he emphasizes the importance of a strong cultural emphasis on education, hard work, and achievement. Dunbar thrived in part because its Black community valued educational attainment and had access to a relatively strong institutional framework that nurtured academic excellence.

The Mid-Century Shift: Post-War Challenges (1940s–1960s)

The post-World War II era marked a shift in both the social dynamics of Washington, D.C., and in the experience of African American students. With the advent of the Civil Rights Movement and the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, schools began to desegregate, and the White population in D.C. largely moved to the suburbs. The result was a demographic shift that led to economic disinvestment in urban schools, including Dunbar. As White families moved away, funding and political support for schools like Dunbar began to erode.

Sowell’s analysis in The Economics of Race suggests that changes in racial integration policies—while well-meaning—often had unintended consequences. For example, while desegregation aimed to integrate Black students into better-resourced schools, it often resulted in the deterioration of Black schools like Dunbar. The increased focus on racial integration meant that local priorities shifted, and the historical strengths of schools like Dunbar, particularly their focus on Black culture and academic excellence, were undermined by systemic budget cuts and neglect.

During the 1960s and 1970s, as Dunbar’s population became predominantly Black and working-class, the school experienced increasing difficulties. With fewer resources and greater societal challenges, Dunbar’s academic performance began to decline. While the school continued to produce some high achievers, it struggled with issues of overcrowding, low graduation rates, and poverty. These were systemic issues that Sowell argues are frequently exacerbated in racially and economically segregated environments. The cultural emphasis on achievement that had supported Dunbar’s success began to wane in the face of these growing challenges.

The Decline: Economic Disinvestment and Policy Failures (1970s–1990s)

The period from the 1970s to the 1990s saw the dramatic decline of Paul Dunbar High School, as the school became increasingly associated with poor academic performance, high dropout rates, and a growing achievement gap. This era is a key example of the issues Thomas Sowell highlights in Discrimination and Disparities, where he argues that economic and social disparities—often exacerbated by ineffective public policy—are key drivers of educational failure in minority communities.

Washington, D.C., experienced an economic downturn in the 1970s and 1980s, which was exacerbated by the loss of manufacturing jobs and the erosion of the tax base. As a result, the District’s public schools, including Dunbar, faced chronic underfunding and a lack of resources. Sowell has frequently argued that the root causes of educational failure are not found in the racial or ethnic backgrounds of students, but in the economic and institutional conditions that shape their environment. By the 1990s, Dunbar had become one of the lowest-performing schools in D.C., with standardized test scores significantly below national averages. The lack of effective leadership, poor student discipline, and the weakening of the educational system in the city were major contributing factors.

A critical issue, according to Sowell, is the mismatch between educational policy and the needs of the local community. Dunbar’s transformation from a center of Black academic excellence to a troubled school mirrors the broader trends in urban school systems across the country, where a reliance on top-down reforms—such as the “No Child Left Behind” initiative—failed to address the underlying problems of poverty, family instability, and community disintegration. These policies, while well-intentioned, did not sufficiently account for the complex factors influencing educational outcomes in underprivileged urban areas.

The Contemporary Era: Reforms and Continuing Struggles (2000s–Present)

In the 21st century, Paul Dunbar High School has undergone multiple attempts at reform. The building was renovated, and the curriculum was revamped, but academic performance has remained persistently low. As of the 2018-2019 school year, Dunbar still struggled with low proficiency rates in core subjects. Only 26% of students were proficient in English Language Arts, and just 14% were proficient in mathematics.

Sowell’s work on education and urban policy in books like The Charter School Solution underscores the difficulty of turning around failing schools when they are mired in broader socio-economic and political challenges. The attempts to reform Dunbar—whether through charter schools, leadership changes, or curriculum revisions—have been only modestly successful at best. Sowell argues that while educational reforms may address surface-level issues, they often fail to address the deeper structural problems that affect schools in disadvantaged communities, including poverty, crime, and family instability.

One of the ongoing challenges for Dunbar, as with many urban schools, is the disconnection between the school and the broader community. Sowell suggests that community values play a significant role in educational outcomes. In The Education of Minority Children, he discusses how the breakdown of family structures and community institutions can contribute to educational failure. Dunbar, once a pillar of the African American community in D.C., now faces challenges that go beyond the classroom, reflecting a larger breakdown in social and cultural supports for students.

The story of Paul Dunbar High School’s rise and fall over the last 100 years provides a window into the broader challenges facing urban education in America. Dunbar’s early success was a product of a strong cultural and institutional commitment to educational excellence. However, as the school faced the cumulative effects of economic disinvestment, changing demographics, and ineffective educational reforms, it fell from its previous heights. Drawing on Thomas Sowell’s insights, it becomes clear that the decline of Dunbar reflects the larger structural issues that plague urban public education: inadequate resources, ineffective policies, and the breakdown of community values that once supported academic achievement. As Dunbar enters its second century, the lessons of its history provide important insights into the ongoing challenges of educational reform in disadvantaged urban areas.

~JH

Bibliography

- Sowell, Thomas. Race and Culture: A World View. Basic Books, 1994.

- Sowell, Thomas. The Economics of Race. Blackstone Audio, 2012.

- Sowell, Thomas. Discrimination and Disparities. Basic Books, 2018.

- Sowell, Thomas. The Education of Minority Children. Hoover Institution Press, 2010.

- “History of Paul Laurence Dunbar High School.” Washington D.C. Public Schools. http://www.dcps.dc.gov.

- Lafer, Gordon. The Race to the Bottom: How the Political Culture of Education in Washington, D.C. Has Led to the Collapse of Public Education. University of Chicago Press, 2019.

- “District of Columbia Public Schools Performance Data.” National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). http://www.nationsreportcard.gov.

Leave a comment